Beginning in the 1880s, a mass emigration of the Galician peasantry occurred. Caused by the backward economic condition of Galicia where rural poverty was widespread, the emigration began in the western, Polish populated part of Galicia and quickly shifted east to the Ukrainian inhabited parts. Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, and Germans all participated in this mass movement of countryfolk and villagers. Poles migrated principally to New England and the midwestern states of the United States.

A total of several hundred thousand people were involved in this Great Economic Emigration which grew steadily more intense until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The war put a temporary halt to the emigration which never again reached the same proportions.

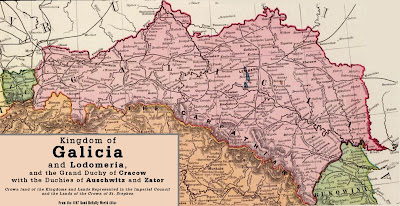

Galicia was the easternmost part of Austria and also the economically least developed part of that country. Its level of development was higher than that of European Russia, but well behind Western Europe. In 1873, the Polish economist Stanislaw Szczepanowski described Galicia as one of the poorest regions in Europe. On a more informal level, the poverty was expressed in a Polish nickname for Galicja and Lodomeria: Golicja i Głodomeria, loosely translated as Naked- and Hunger-Land. In 1888 the average income per capita did not exceed 53 Rhine guilders (RG), as compared to 91 RG in the Kingdom of Poland (ruled by Russia), 100 in Hungary and more than 450 RG in England at that time. The taxes in Galicia were relatively high and equalled to 9 Rhine guilders a year (ca. 17% of yearly income), as compared to 5% in Prussia and 10% in England.

No country of the Austrian monarchy had such a varied ethnic mix as Galicia. At the turn of the Twentieth Century, Poles constituted 78.7% of the whole population of Western Galicia, Ukrainians 13.2%, Jews 7.6%, Germans 0.3%, and Armenians, Czecks, Slovaks, Hungarians, Roma and others 0.2%.

Religious denominations were fewer, with the Poles being Roman Catholic, the Ruthenians (now mostly calling themselves Ukrainians) belonged to Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church, and the Jews belonging to the branch of Orthodox Judaism known as Hasidism.

The average life expectancy was 27 years for men and 28.5 years for women, as compared to 33 and 37 in Bohemia, 39 and 41 in France and 40 and 42 in England. Also the quality of life was much lower. The yearly consumption of meat did not exceed 10 kilograms per capita, as compared to 24 kg in Hungary and 33 in Germany. This was mostly due to much lower average income.

Thus, due to the hunger, cold and ethnic oppressions the Galician peoples were forced to look for refuge in America and elsewhere. With the abolishment of serfdom in 1848, immigration became possible. For travel across the border local authorities issued provisional passes or permits.

The journey to America was long, costly, and tedious. The majority of emigrants came from remote villages. Peasants began their journey with teams of horses or on foot, to get to the nearest railroad station. In the case of Athanasius, he may have boarded the train at Chabowka, which had rail service since 1884. Zakopane did not get a rail line until 1899, long after he left.

In the 1890s there were many instances of people using rafters’ passports to travel up the nearby Wisła (or Vistula) River all the way through Poland, passing through Krakow, Warsaw, Toruń, and Gdańsk, where it emptys into the Baltic Sea. From there the traveler would head for Hamburg for ships passage to America or elsewhere.

As the extent of emigration increased, the regulations were changed to discourage removal. In the case of men of military age, immigration was outright banned.

In Galicia raids were usually conducted most often at railroad stations. Agents posted there observed the travelers, and if there was even the slightest suspicion of illegal emigration they seized the persons suspected and turned them over to police commissioners. Their documents legality were thoroughly checked, as well as their financial means and their status in regard to military service.

Toward the end of the 19th century, when the wave of emigration reached its greatest height, the partitioning powers introduced more and more restrictions—but the number of emigration permits issued differed more and more from the actual state of affairs. In the years 1886-1890 the Prussian border was closed to emigrants from Russia and Galicia. Issuing passports was limited to a minimum.

In mid-1893 the Galician governor’s office issued a circular, instructing officials to use all legal and moral means to keep people from emigrating without good cause. The campaign included clergymen, teachers, and military policemen. In the years between 1870 and1890 even the newspaper Gazeta Lwowska printed articles that were intended to discourage emigration, giving false information on numerous ship sinkings and other catastrophes on the ocean. The authorities even confiscated letters from abroad, which touted the New World lands of milk and honey.

Occasional postings on genealogical histories, mostly of my family, but also including interesting non-family material I found while doing research.

My main interests are the Newton, Dziubinski, Gruetzmacher, Hutt, Snyder, Gerard, Randolph, and Villard families.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

Dziubinski Info

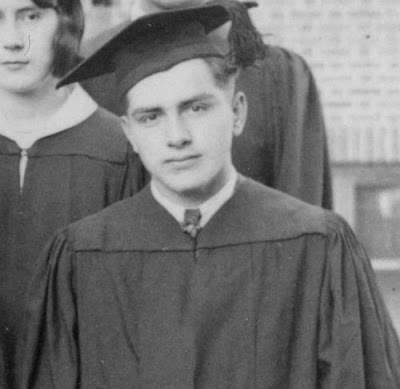

Brother Tom provided a photograph and some newspaper clippings to me the other day which offered new (to me) information about the Dziubinski's. The photograph is of Emil Dziubinski in 1931 with his Holdingford High School classmates. (I have the full picture, with names, available to those interested.) Emil was Irene's older brother who died in the October, 1931 car accident in Wisconsin. In that same accident, Irene's mother Anastasia (or Nettie, as she was affectionately known), was also killed and sister Helen lost her leg.

In one of the other clippings Tom discovered is the obituary for Irene's father Athanasius. It says that he was "born in Nowysak, Poland" and "grew up and attended school in Zakopony, Poland". Nowy Sacz is both a town and county in southern Poland, very near the border of present-day Slovakia. Further southwest is Zakopane, also a village in Nawy Sacz county, sitting almost on top of the border.

In the 19th century, Zakopane was the largest center for metallurgy in Galicia — and later with that of tourism. It grew greatly over the 19th century, as more and more people were attracted by its salubrious climate, and soon developed from a small village into a climatic health resort with 3,000 inhabitants in 1889, eight years before Athanasius immigrated to America.

I wonder why Anthansius, situated in a apparently prosperous if not down-right booming town, would decide to head off to America. The obituary notes that in addition to being a farmer, he was also a cabinet maker. As a 23-year-old with such a marketable skill, I am trying to imagine what influences pressured him to leave Poland.

Just prior to his birth in 1874, Galicia, as this area of southern Poland was called, was de facto an autonomous province of Austria-Hungary, with Polish and, to a much lesser degree, Ukrainian or Ruthenian, as official languages. The area had been racked by the Austro-Prussian War, peasant insurrections, political revolutions and military actions in response. Galicia was now subject to internal arguments between Vienna and the Poles in the west and the Ruthenians and Ukrainians in the east.

I had always assumed Athanasius has immigrated to America to get away from the ongoing military situation. And while that may have been a part of his decision, it was the economic situation of Galicia that was most likely the main impetus for such a drastic removal. I will discuss the economics in the next posting.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)